Introduction of Ruby language

Ruby is simple in appearance, but is very complex inside, just like our human body.

Ruby is an interpreted, high-level, and general-purpose programming language.

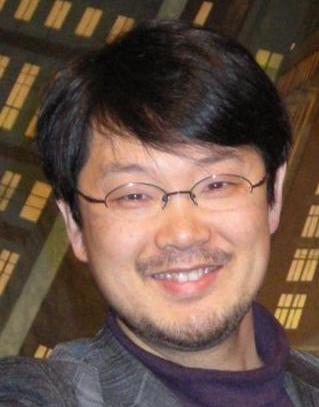

It was designed and developed in the mid-1990s by Yukihiro "Matz" Matsumoto in Japan.

Ruby is dynamically typed and garbage-collected. It supports multiple programming paradigms, including procedural, object-oriented, and functional programming.

Its creator, Yukihiro “Matz” Matsumoto has often said that he is “trying to make Ruby natural, not simple,” in a way that mirrors life.

Yukihiro Matsumoto (Matsumoto Yukihiro, born 14 April 1965), also known as Matz, is a Japanese computer scientist and software programmer best known as the chief designer of the Ruby programming language and its reference implementation, Matz’s Ruby Interpreter (MRI). His demeanor has brought about a motto in the Ruby community: “Matz is nice and so we are nice,” commonly abbreviated as MINASWAN. (source)

Let’s understand the important features of the language briefly reviewed below.

Interpreted

An interpreted language is a type of programming language for which most of its implementations execute instructions directly and freely, without previously compiling a program into machine-language instructions. The interpreter executes the program directly, translating each statement into a sequence of one or more subroutines, and then into another language (often machine code).

High Level

High-level language refers to the higher level of abstraction from machine language. Rather than dealing with registers, memory addresses and call stacks, high-level languages deal with variables, arrays, objects, complex arithmetic or boolean expressions, subroutines and functions, loops, threads, locks, and other abstract computer science concepts, with a focus on usability over optimal program efficiency.

General Purpose

Designed to be used for writing software in the widest variety of application domains. Conversely, a domain-specific programming language is one designed to be used within a specific application domain.

Dynamically Typed

The type is associated with run-time values, and not named variables/fields etc. This means that a programmer can write a need not have to specify types every time. Conversely, type of a variable is known at compile time for a Statically Typed.

name = 'Ruby'

# variable name is given data type as String by Ruby Interpreter

name = 100

# variable name data type is changed to Integer by Ruby Interpreter

In above example, you can easily understand how the data type of the variable name can be switched easily

since during compile time data type is not checked.

Garbage Collection

In computer science, garbage collection (GC) is a form of automatic memory management. The garbage collector, or just collector, attempts to reclaim garbage, or memory occupied by objects that are no longer in use by the program.

Check this article to understand the whole concept, design, type and process of garbage collection in Ruby in details.

The strategies of Garbage collection has evolved from Mark & Sweep to Incremental Sweep in Ruby 2.2. More can be found here.

Philosophy of Ruby

In an interview Matz discussed the Philosophy of Ruby where he described why he designed Ruby. Click here for full interview.

No Perfect Language

Matz says, “Instead of emphasizing the what, I want to emphasize the how part: how we feel while programming. That’s Ruby’s main difference from other language designs. I emphasize the feeling, in particular, how I feel using Ruby. I didn’t work hard to make Ruby perfect for everyone, because you feel differently from me. No language can be perfect for everyone. I tried to make Ruby perfect for me, but maybe it’s not perfect for you.

Freedom and Comfort

Matz says, “Ruby inherited the Perl philosophy of having more than one way to do the same thing. I want to make Ruby users free. I want to give them the freedom to choose. People are different. People choose different criteria. But if there is a better way among many alternatives, I want to encourage that way by making it comfortable.”

The Joy of Ruby

Matz says, “You want to enjoy life, don’t you? If you get your job done quickly and your job is fun, that’s good isn’t it? That’s the purpose of life, partly. Your life is better. I want to solve problems I meet in the daily life by using computers, so I need to write programs.”

The Human Factor

Matz says, “Often people, especially computer engineers, focus on the machines. They think, “By doing this, the machine will run faster. By doing this, the machine will run more effectively. By doing this, the machine will something something something.” They are focusing on machines. But in fact we need to focus on humans, on how humans care about doing programming or operating the application of the machines. We are the masters. They are the slaves.”

Principle of Least Surprise

Matz says, “The principle of least surprise means principle of least my surprise. And it means the principle of least surprise after you learn Ruby very well. For example, I was a C++ programmer before I started designing Ruby. I programmed in C++ exclusively for two or three years. And after two years of C++ programming, it still surprised me.”